"A world where prisons serve no purpose"

Interview with Kony Kim of the Bay Area Freedom Collective

Hi, TTSG fam.

Tammy here with a must-read pod extra.

This week, I spoke with an old friend, Kony Kim, an activist lawyer and organizer with the Bay Area Freedom Collective. Kony represents incarcerated men in parole hearings at San Quentin State Prison, the oldest correctional facility in California and the only one with a death row.

Recently, San Quentin has made national news for its fatal, preventable coronavirus outbreak: More than 2,200 imprisoned men and workers have tested positive, and 25 have died. (The total prison population, as of June, was 3,462 people.)

San Quentin continues to be on lockdown, depriving the men inside from in-person contact with friends and family, attorneys, teachers, and counselors. Kony made her last visit in mid-March, and now attends parole hearings by Skype.

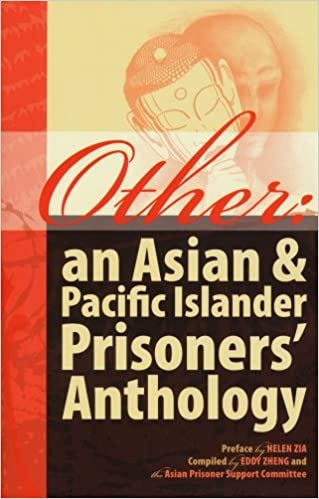

I asked her about the Covid-19 outbreak, prison abolitionism, and why she chose to expand her predominantly Black and Latino client base to include Asian Americans (like Sak, her former client, pictured above). Below is an edited transcript of our conversation.

If you’d like to connect with, or donate your money and time to, the Bay Area Freedom Collective, please do so via Patreon (https://www.patreon.com/bafc), Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/bayareafreedom), or email (hello.bafc@gmail.com).

And thank you for reading and subscribing to TTSG (https://goodbye.substack.com).

Down with jails; up with estate taxes,

Tammy

P.S. – Enjoy our hard-earned Labor Day weekend. Go, workers!

///

Tammy: Kony, thanks so much for doing this, and welcome to Time to Say Goodbye. It’s great to have you on.

Kony: Thank you for having me.

T: Maybe we could start with an overview of what your job is, or what your many jobs are.

K: Sure. Right now, I’m a parole hearing attorney. I started volunteering in prisons about a decade ago, but in terms of legal advocacy, I’ve been working in this area for seven years—the past two years as a solo practitioner, running an extremely unprofitable law practice out of my home office. [Laughs.] I basically prepare my clients for parole hearings and then represent them at those hearings. My clients are almost all lifers—people sentenced to life with the possibility of parole—and they are labeled as “violent offenders.” They are all people who are doing time for having committed acts of violence, and pretty much all of them are people who’ve been exposed to unconscionable levels of neglect and trauma in their childhood.

T: Who are they in terms of race and age?

K: When I first started working as an attorney, I was at a nonprofit, and most of my clients there were older, in their fifties, some in their sixties or seventies. They were diverse in terms of racial background. I had a lot of Black clients and then a couple Latino clients and a couple of white clients. When I left to start my own practice, I had a desire to work with clients who look like me. I reached out to the Asian Prisoner Support Committee and had them refer some people to me. In my solo practice, maybe about half my clients are of Asian descent.

T: What kinds of prisoners are in San Quentin?

K: San Quentin is classified as a level two facility, which means it’s lower security, and there’s a lot of programming there, so most people who are serious about improving their life prospects want to go there. Because of the medical facilities, it’s also a place where people with medical vulnerabilities will go, so maybe a third of the population has some kind of medical issue or is classified as high-risk medical.

T: So it seems all the more strange, then, that they were transferring people into San Quentin who were potentially Covid-positive.

K: That decision was mind-blowing. I don’t even know what to think about it. It was either completely incompetent or callous, or both. The idea was to relieve overcrowding at the California Institute for Men, where there was an outbreak of seven hundred, and someone decided to transfer them, even though they hadn’t been tested recently. Some hadn’t been tested for three weeks before the transfer. On paper, the intention was to relieve pressure down south, but the result was, they created a gigantic outbreak where there had been zero cases before that. What else is mind-blowing about the transfer is, after the men were transferred to San Quentin from CIM, they weren’t tested upon arrival. They were placed in the institution and shared dining and showers for a couple days before they were tested. It was entirely preventable and extremely tragic.

T: What have you heard most recently from your clients about Covid transmissions and the general situation?

K: The official numbers are down a lot, and it looks like the number of active cases is below twenty now. I haven’t been getting as many letters from clients as I was at the height of the outbreak. But what my clients consistently tell me is that it’s worse than what the officials say. They’re still seeing people “falling out”—going out to medical—and people are still suffering the symptoms. People still don’t have access to programs, to nutritious food. Their access to showers and yard time and phone calls is erratic. Sometimes, they have to choose between taking a shower or calling their loved ones. They can’t do both, and the next chance they have to do so is five days later.

T: Tell me about the letters you were getting from clients at the height of the outbreak.

K: At some point, I’m pretty sure every single one of my clients got sick. I heard from all of them except for one—15 out of 16. They were telling me about the chaos around them. The phrase is “man down.” That’s what they yell when someone needs to go to medical because they’re literally on the ground. For a while, it was just twenty-four-hour lockdown for weeks, and they were telling me about how there was no more hot food because the outbreak had hit the kitchen staff, and they couldn’t find a vendor willing to come provide food. So people were getting two sack lunches a day, which consisted of thin two slices of bread, a little bologna, an apple, and a cracker. One of my clients was telling me his cellie [cellmate] was definitely sick and refusing to report his symptoms because he didn’t want to get sent to solitary confinement. They didn’t have places to quarantine people because all of the cells have open bars. At some point they ran out of space in solitary, so they were just leaving people in their cells, even if one tested positive and one tested negative. And then they created a makeshift hospital out of the industrial warehouse in San Quentin to put the sick people. They put two hundred beds in there. My client was telling me, that’s the place they got sued over having asbestos.

T: San Quentin is a facility that California takes a lot of pride in, so what do you make of this—that they were willing to treat the population this way?

K: It seems like people just gave up. It was clear that the only way to deal with the outbreak was to decarcerate, and they just didn’t want to do that. They had a memo that a bunch of correctional-health experts had prepared in June. On June 15, a group of health professionals called Amend—they had toured San Quentin when some of the first cases appeared, and did a full audit of the system and the building—wrote a really detailed memo of what needed to happen from their public-health perspective. There were a lot of staffing changes and also physical changes to buildings that they recommended, but they also said, ‘There’s no way this can be handled without decarceration by about fifty per cent.’ And nobody who had power to make changes wanted to seriously consider that route.

T: Releasing prisoners was discussed early on, as soon as Covid was hitting. Governor Gavin Newsom has been saying that he’s decarcerated quite a few people, but what’s your view of the numbers of people who have actually been decarcerated at San Quentin and other facilities?

K: It’s just a drop in the bucket. I think it’s just for show. By the end of August, the number released was about eight thousand, whereas the overall prison population is nearly one hundred thousand. The system is still at one hundred and eight per cent capacity. It’s a good start, a good half-step in the right direction, but it’s not nearly enough. I believe the population of San Quentin specifically has been reduced by three or four hundred or so. That’s just [Newsom] saying, ‘I’m doing something about it. I’m going to throw you a bone.’ It’s not enough to make a difference, and I think everyone knows that. In doing so, he’s shown his true colors by carving out exceptions to the early releases. Specifically, excluding people convicted of violent crimes who are actually some of the lowest-risk people in the prison population, especially those who have served decades already and are senior citizens, and have done the most work to change their lives while inside.

T: Even when we’re talking about Black Lives Matter, prison reform, and decarceration, it’s always focused on non-violent offenders. Why do you choose to represent people who’ve been convicted of violent crimes, and what do you think of this distinction between “good prisoners” and “bad prisoners?”

K: The dichotomy between “violent” and “nonviolent offenders” is extremely problematic. First, it’s somewhat artificial. Several of my clients who were convicted of murder never physically harmed anyone. They were with a group, and it was a crime partner who pulled the trigger or beat someone up. Second, it’s just not helpful. If prison is inhumane and doesn’t work, if there are better responses to harm, let’s find better responses to all kinds of harm. Why is it less important to find humane and constructive solutions to violence as opposed to non-violent harm? Third, and most importantly, these labels freeze people in time. People who commit violence can and do transform their lives.

T: Why did you decide to work with “violent offenders”?

K: I didn’t really go into this work consciously choosing to work with people who have committed violence, but I think that I was drawn to working with people in prison because I’m drawn to trauma. [Laughs.] Because I’m drawn to working with trauma and resilience. And I think part of my original motivation, which I didn't become conscious of until I reflected on it many years later, is that I had my own unhealed trauma to deal with. I didn't have a name for it, I didn’t know how to talk about it. I was fortunate enough to meet people in prison who had done that work on themselves and feel that in their presence.

T: Were these people prisoners or workers in the prison?

K: I had taken a restorative justice class in law school, and as part of that we got to visit a restorative justice group in San Quentin. So we sat in a circle with guys who’d completed the program and done the work. They were introducing us to what restorative justice meant and how to apply it.

T: What does restorative justice mean in this context?

K: Restorative justice is an approach to conflict and harm that is focused on repairing the harm and repairing the relationships that were broken—and encouraging healing and accountability among everyone involved, as opposed to looking for a way to punish and looking for a way to label who’s the “offender” and who’s the “victim.” Restorative justice is about recognizing that multiple people can be harmed and that the same person who has harmed others can also be someone who’s been on the receiving end of harm, and vice versa.

T: A lot of liberals and leftists can imagine what restorative justice looks like in terms of drug crimes or petty crimes, but are much less clear on what a non-punitive approach looks like for rape or murder. In working with your clients who have committed violent offenses, what sorts of restoration or reconciliation are possible with families and victims?

K: For most people in prison, they’re prohibited from contacting anyone who was directly impacted by their crime. I have a client who sexually assaulted multiple women. He's a bogeyman in the public imagination. But when I heard his story, he’s had one of the most traumatic childhoods that you can imagine, and, perhaps not shockingly, he himself was a victim of sexual assault in his childhood, multiple times. When I first started working with him, he actually didn’t see the connection between his own trauma and what he’d done to others. And I think that’s in part because you can’t talk about sexual assault in prison. Because whether you’re somebody who experienced it or somebody who did it, that marks you as a target. My clients find restoration through healing themselves, learning to forgive themselves first. That empathy leads to people wanting to give back—people mentoring other, younger individuals.

T: With Black Lives Matter and the last decade of police-reform and decarceration conversations, a lot of people have started to identify as abolitionists. Do you consider yourself an abolitionist? What is your view of prisons and the system your clients have gone through?

K: My views have really evolved over the course of working in this area. When I first started, I did not have a political orientation. I knew nothing about the criminal legal system or abolition, and my interest in it came from me really caring about the people, getting curious about their lives, what they’d been through. Also, what were their chances of building a good life after they got out? That led me to start shifting my academic research toward prisons and also my legal career goals to prisons. I was exposed to abolitionism as I was doing that research, and I liked the theories behind it but didn’t give it that much thought.

I think everything clicked for me probably earlier this year. As I was doing this work as an attorney, I had been so enmeshed in my clients’ stories and trying to get them out [of prison] and working really hard to hold their trauma and hopes and expectations and not really thinking about the larger system. And when Covid hit and all of a sudden I could no longer visit my clients, suddenly I had more time to sit back and think and reflect, and then the murder of George Floyd happened, and there were images of police brutality everywhere. Then everything started to come together for me. Abolition is about fundamentally transforming our relationships to each other. It’s not just about the bigger system. It’s about building a world where people like my clients get the love, care, and resources they deserve as young people, so that they don’t grow into adults with unhealed wounds that lead to violence. That’s a world where prisons, as we know them, serve no purpose.

T: One of the most public things to come out of San Quentin is the podcast Ear Hustle, and I was thinking about some of the guys on that show, and other texts I’ve read by people who’ve been in prison, who say that prison was horrible but it’s necessary to protect people. Or that there are possibilities for growth and treatment in there that, because our society is structured in such an awful way, don’t exist on the outside. Do you have clients who see abolitionism and think, ‘Oh, sure, that’s easy to say, but on some level, in the society we have, prison is a necessary evil’?

K: Definitely. I’ve had some clients basically say, ‘In here, in prison, you see certain people that you know do not belong in society.’ Also, some of them say, ‘Prison is the best thing that happened to me. If I hadn’t come here, I would’ve ended up dead or doing something worse. Prison was the place where I was given the chance to turn my life around.’

T: What do you say to that? That’s an indictment of all of us: that we’ve allowed people to live in such dire situations. Do you feel that it’s your responsibility to stretch their imagination or just accept that it’s the truth they’ve lived?

K: It depends. If we’re in the middle of parole prep, I might table that discussion for another day. [Laughs.] But with clients who’ve come home [been paroled] and become friends of mine, we have more space to talk about those things. So it’s a longer term conversation. I don’t think I necessarily see it as my job to change their mind, but I just try to ask them questions and figure out, ‘What are the assumptions behind that?’

T: Can you talk about the reentry work you’re doing?

K: In June of this year, a couple of formerly incarcerated friends and I decided to create a reentry support community slash mutual aid network for people coming home. Part of the reason for that was a feeling that, although there are great nonprofits doing great work in the community, there wasn’t enough on-the-ground support for people coming home. There’s some logistical stuff and also the social-emotional stuff. First of all, picking people up from the gate [of the prison], taking them safely to their destination, checking in with the parole agent, taking them for their first meal—a welcome home—making sure they have hygiene supplies or if they need clothes. A lot of people just come out with the clothes on their back from prison. Also, helping them learn how to navigate the world, because, if they’ve been away for twenty, thirty years, they may not know how to use public transportation, how to drive, how to go shopping for groceries. The amount of choice is overwhelming. How to use a debit card. It’s helpful if they can learn that from peers who went through the same thing. They also need to get an ID—signing up for benefits. And for people who aren’t citizens, they need to get a work permit. That’s a lot of paperwork. And of course there’s the social emotional support—being able to feel a sense of belonging and acceptance as they’re adjusting to a world that’s completely foreign to them.

T: The people who need to get work permits, what is their status? Are these the Asian prisoners you referenced earlier?

K: The work-permit requirement applies to people who, either they never had legal-permanent-resident status or they lost it because of their conviction. So I believe that most of them, if not all of them, are under threat of deportation. And for some of them, that threat is more real than others. It all depends on the stance of that particular country, whether they are accepting deportees or not from the U.S.

T: The Asian Prisoner Support Committee, do they primarily organize behind Southeast Asians who settled here as a result of war?

K: When I first became a solo practitioner and reached out to APSC for referrals, they sent four or five people my way, and pretty much all of them fall under that category. Their parents, they were refugees; their parents had experienced war, a lot of instability. Some of them were born in refugee camps, some of them lost siblings, trying to escape from Vietnam to other countries, and then came to the United States and experienced further instability and marginalization, stigmatization, a lot of difficulties adjusting to a new culture, and being raised by parents with unhealed trauma.

T: Why were you interested in representing Asians?

K: I’m not really sure why. Maybe I just felt a desire to work with clients who look like me. [Laughs.] This work is so much about delving into people’s childhoods and how their social, cultural, and economic contexts shaped them, and I was learning so much about people with backgrounds very different from mine, which I really appreciated, and also finding threads of connection—like what it feels like to not feel loved or seen in your own family and have that impact your sense of self growing up. I was really curious about what it would feel like to find those threads of commonality with people who are of Asian descent and also have an immigrant background.

T: The last time I saw you, you had the edited volume made by APSC. What has the organizing and cultural production of this community looked like?

K: The anthology project is for the second edition of Other: An Asian & Pacific Islander Prisoners’ Anthology [edited by Eddy Zheng]. It was basically a collection of writings by people of Asian descent who were either currently or formerly incarcerated. Nothing like that existed back in 2002, when it was published. That anthology became widely read in Asian American studies programs, and a lot of time had passed since, so a couple years ago, there was a feeling that there should be a new one—and also one that encompassed issues of deportation. The thought was to show different stories that could give people a sense of the immigration-to-school-to-prison-to-reentry-to-deportation pipeline. [Laughs.]

T: Because it’s transnational—some of the people are living in Cambodia.

K: Exactly. And just thinking about the role of imperialism in creating these refugee crises and then failing to care for the families who fled here. That’s why many of my clients, the young people, ended up in gangs and then ended up in prison. So the idea is to show what those connections are and to highlight the profound injustice and nonsensical nature of further punishing people after they do their time by sending them back to a country where they don’t know anybody and have no support.

T: What’s been your experience working across class, race, and gender? The Asian prisoners may share certain experiences with you, but you’ve had an elite education and come from resources. How do you get them to trust you?

K: I was definitely feeling the race, class, and gender differences back when I was volunteering as an instructor or a restorative justice participant. My response back then was just to ignore it. [Laughs.] And truth be told, I was horrible about boundaries. I just wanted to be nice and normal with everybody. If somebody acted creepy or asked me for favors, I didn’t know how to say no.

I learned how to carry myself differently over the course of my volunteering and to be more aware of how I’m perceived as a young-looking Asian female coming in from the outside—and how to set a tone that’s conducive to mutual respect. As an Asian female, I’m going to be objectified sometimes. That’s first thing they notice. In terms of getting people to trust me, trust is something I’ve earned over the course of several years, volunteering and doing pro bono advocacy in the San Quentin world. What’s helpful is that I’ve been around so long, and I’ve always been consistent. I might have been naive early on, but people know I’m someone who cares, someone who really listens, and I keep my word.

/ / / /

Whew, heady stuff.

Thanks again for supporting TTSG (https://goodbye.substack.com), and please reach out via Twitter (@ttsgpod) or email (timetosaygoodbyepod@gmail.com)!

New episode coming soon.